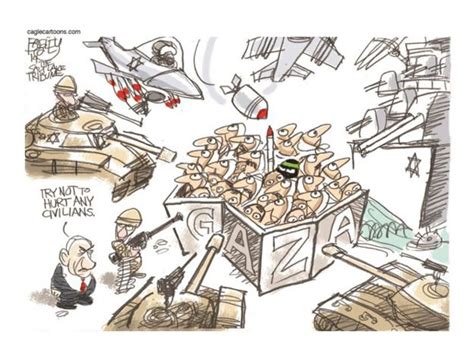

Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s statement that “we have to see Hamas demilitarised” represents a marginal improvement over calls for Hamas’s complete disbandment, yet it fundamentally misses the strategic point. Rather than focusing on managing the symptoms of the Israel-Palestine conflict, the international community should address the root causes that created Hamas in the first place.

The Current Approach

Wong’s position reflects the broader international consensus that places Hamas demilitarisation, hostage releases, and Palestinian Authority reforms as prerequisites for Palestinian recognition and progress toward a two-state solution. This approach suffers from several fundamental flaws:

• By demanding that Palestinians abandon their most effective forms of leverage before receiving meaningful concessions, the current approach ignores fundamental negotiation dynamics. It essentially asks the victims of occupation to solve the problems created by that occupation before the occupation itself is addressed.

• Making Palestinian recognition contingent on Hamas demilitarisation effectively gives Hamas veto power. The most radical elements can block progress simply by maintaining their military capabilities.

Successful conflict resolution processes elsewhere provide a model. In these cases, disarmament occurred as a result of political settlements, not as a precondition for such settlements.

Israel’s Creation of Hamas

There is little acknowledgement of Israel’s role in the creation of Hamas. During the 1970s and 1980s, Israeli authorities deliberately supported Ahmed Yassin’s Muslim Brotherhood in an attempt to weaken the secular Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO).

Israeli officials believed they could manage Palestinian politics by fostering an Islamic alternative that would be more cooperative and less threatening. Multiple Israeli officials, including Brigadier General Yitzhak Segev and former Civil Administration director Efraim Sneh, have acknowledged providing financial assistance to Hamas’s precursor organisation.

This support continued until 1989, when Hamas launched its first attacks on Israelis. The pattern repeated in the 2010s-2020s, when Israeli officials encouraged Qatari funding to Hamas, which Israeli intelligence later concluded contributed to the October 7, 2023, attacks.

Israel’s attempts to manipulate Palestinian politics while maintaining occupation consistently backfired, creating more radical adversaries. The lesson is not that Israel should have chosen different Palestinian partners, but that attempts to manage Palestinian political development while maintaining the underlying conditions of dispossession are doomed to failure.

Root Causes First

The proposed alternative reverses the current sequence by addressing root causes before demanding symptom management:

- Stop the killing: Break the cycle of violence that serves extremists on both sides

- Free the hostages: Address immediate humanitarian concerns as part of a broader settlement

- Israeli withdrawal from Gaza: Test Palestinian self-governance in a manageable context

- Schedule Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories: Address the core issue driving the conflict

- Implement a genuine two-state solution: Provide a framework for both peoples’ national aspirations

Israel could agree to that now, and Hamas would have no choice but to follow. This recognises that Hamas’s power derives from its role as a resistance movement against occupation. Remove the occupation, and Hamas’s raison d’être largely disappears.

This approach is grounded in successful conflict resolution experiences:

- Northern Ireland: The Good Friday Agreement did not demand IRA disarmament before negotiations. Instead, it created political frameworks that made armed struggle unnecessary, with disarmament following as a consequence of political progress.

- South Africa: The African National Congress maintained its military wing throughout apartheid but abandoned armed struggle when the apartheid system itself was dismantled.

- Bougainville: The 2001 Bougainville Peace Agreement did not demand that the Bougainville Revolutionary Army disarm before political negotiations. Instead, it established a “three pillars” framework where autonomy came first, followed by gradual weapons disposal linked to political progress, and culminating in an independence referendum. The BRA transformed from a secessionist army into participants in democratic governance as the root cause—denial of self-determination—was addressed through the autonomy arrangement and promised referendum.

Australian Policy Implications

Australia’s current approach reflects tensions between stated principles and practical constraints. While supporting the two-state solution in principle, Australia has been reluctant to take concrete steps that might pressure Israel to implement these principles.

Australia’s position as a middle power with significant regional relationships could make it an effective advocate for innovative approaches. Unlike the US (seen as biased toward Israel) or European countries (carrying colonial baggage), Australia could serve as a more neutral mediator.

Practical Challenges

- The current Israeli government shows little interest in meaningful concessions and has actively undermined the two-state solution through settlement expansion.

- Implementation assumes Palestinian leaders could deliver on commitments to transform militant groups, despite ongoing divisions between Fatah and Hamas.

- The US remains Israel’s most important ally and has historically been reluctant to pressure Israel on core issues.

However, recent developments suggest growing international momentum: France’s decision to recognise Palestinian statehood in September 2025 and the UN conference on the two-state solution indicate shifting dynamics.

The choice between current symptom management and an alternative framework represents a fundamental moral and strategic decision about conflict resolution. The current approach asks the weaker party to solve problems created by the stronger, while allowing the status quo to persist.

Sustainable peace requires justice, not just the absence of violence. By addressing root causes, it creates conditions that naturally lead to militant movements’ transformation into conventional political parties.

Conclusion

Wong’s statement represents incremental progress but remains trapped in failed paradigms. Whilst demilitarisation sounds positive, the real insight lies in recognising that sustainable solutions require removing the reasons Hamas was created in the first place.

The international community has extensive experience with successful conflict resolution. The key lesson is that sustainable disarmament occurs as a result of political settlements addressing underlying grievances, not as a precondition for such settlements.

Australia and other middle powers could advocate approaches that address root causes rather than managing symptoms. This requires courage to challenge failed approaches, even when they are diplomatically convenient. Only by embracing this more strategic framework can there be genuine hope for sustainable peace in the Middle East.

The choice is clear: continue with approaches that have failed for decades or embrace a framework that addresses the fundamental causes of conflict – the moral imperative points toward the latter option.

David Higginbottom

31 July 2025